How Did The Greeks View Ancient India?

Did they think India too righteous to invade anyone? That it had no slaves? From Herodotus and Nearchus, to Megasthenes and Arrian — let’s understand the Greek Perspective on Ancient India.

The Greeks didn’t always know India. Early mentions of the subcontinent are scattered and vague.

Hecataeus of Miletus, writing in the 6th century BCE, refers to people along the Indus using names like “Indi,” “Indus,” “Argante,” and “Opia.”

A century later, Herodotus tells us that King Darius I of Persia sent a Greek explorer, Scylax, to trace the Indus River around 515 BCE.

But most of what’s attributed to Scylax was actually written much later, likely in the 4th century BCE.

Nevertheless, Herodotus offers us one of the earliest Greek accounts of India. His descriptions are a mix of observation and hearsay:

“As far as India, Asia is an inhabited land; but thereafter, all to the east is desolation, nor can anyone say what kind of land is there.”

He places India at the eastern edge of the known world, noting its vastness and the mysterious lands beyond.

He also describes tribes who lived off fish in marshy regions, and others who refused to harm any living creature, surviving instead on vegetables.

These weren’t just passing details for him — they were signs of how fascinating, the Indian world seemed from the Greek point of view.

"The tribes of Indians are numerous, and they do not all speak the same language — some are wandering tribes, others not. They who dwell in the marshes along the river live on raw fish, which they take in boats made of reeds, each formed out of a single joint. These Indians wear a dress of sedge, which they cut in the river and bruise; afterwards they weave it into mats, and wear it as we wear a breast-plate. Eastward of these Indians are another tribe, called Padaeans, who are wanderers, and live on raw flesh.

There is another set of Indians whose customs are very different. They refuse to put any live animal to death, they sow no corn, and have no dwelling-houses. Vegetables are their only food.

All the tribes which I have mentioned live together like the brute beasts: they have also all the same tint of skin, which approaches that of the Ethiopians.

Besides these, there are Indians of another tribe, who border on the city of Caspatyrus, and the country of Pactyica; these people dwell northward of all the rest of the Indians, and follow nearly the same mode of life as the Bactrians. They are more warlike than any of the other tribes, and from them the men are sent forth who go to procure the gold. For it is in this part of India that the sandy desert lies. Here, in this desert, there live amid the sand great ants, in size somewhat less than dogs, but bigger than foxes."

In a rather strange tale, Herodotus also describes the Callatiae, an Indian tribe that, he claims, ate their dead to honour them.

The Callatiae, he says, found Greek cremation just as disturbing as the Greeks found their own rites.

For Herodotus, it was a clear sign of how culture shapes our conscience.

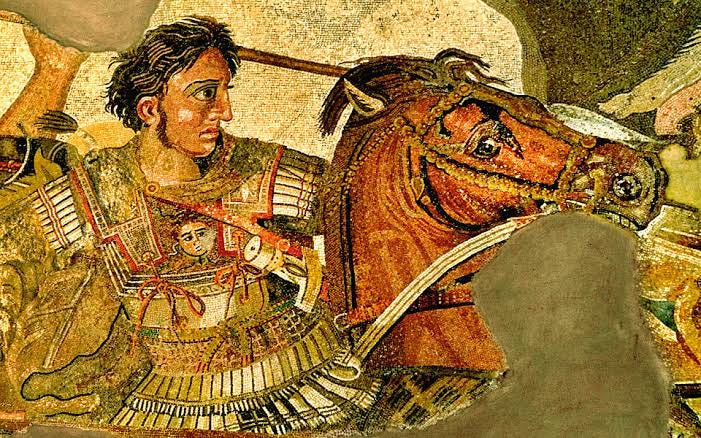

India, as a place, is completely missing from Homer, Pindar, or the Athenian playwrights. That changed dramatically after Alexander’s campaigns in the late 4th century BCE.

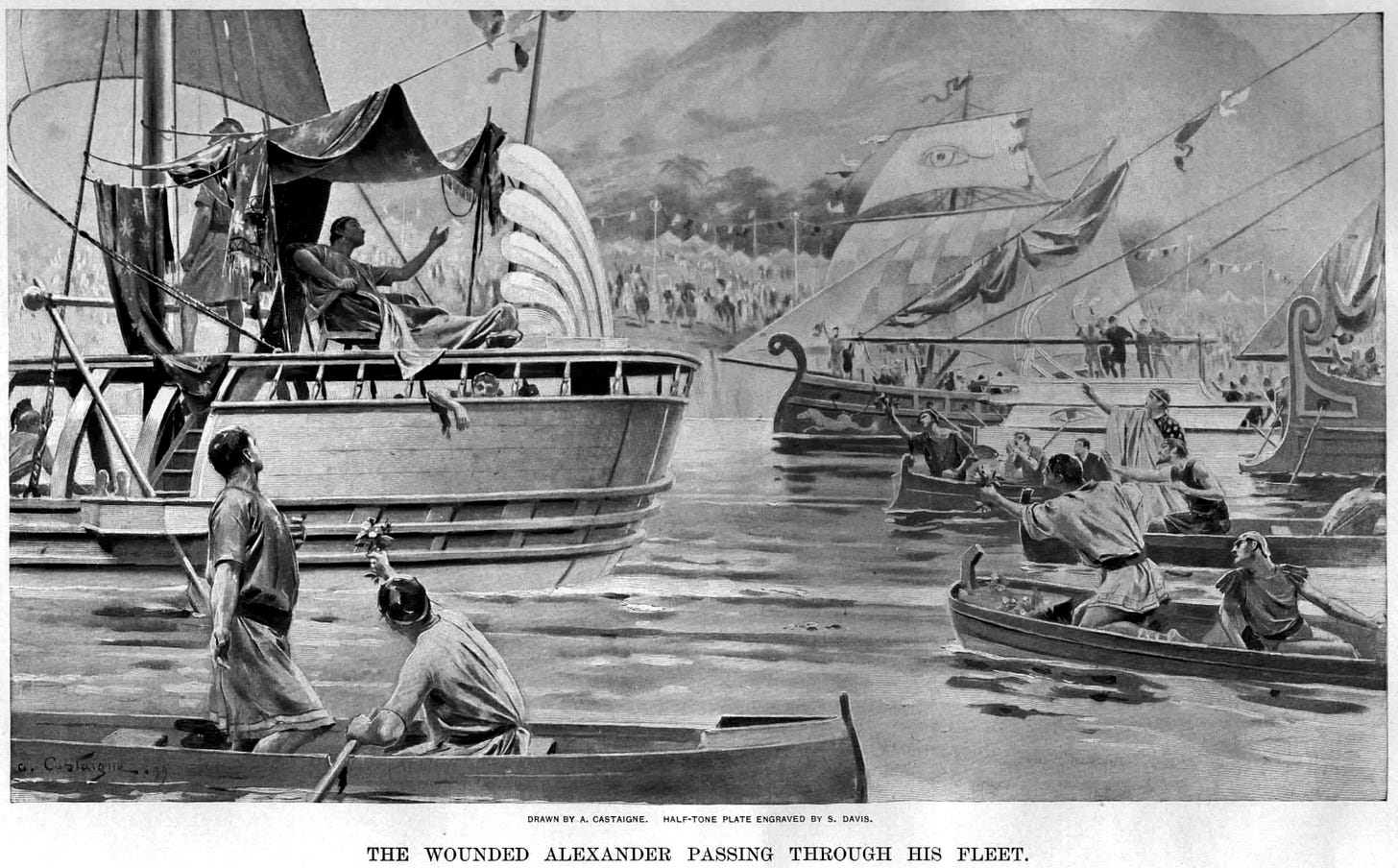

Suddenly, India was real, not just a distant rumor. Nearchus, one of Alexander’s officers, left an account of his journey from India to Babylon. Onesicritus, a naval captain, wrote about Sri Lanka.

But the most famous Greek to write on India was Megasthenes.

Sent as an ambassador by Seleucus I to the court of Chandragupta (the “Sandrocottus” of Greek texts), Megasthenes wrote Indika, a sweeping account of Indian history, customs, and mythology.

Others followed. Deimachus wrote during Bindusara’s reign.

Patrocles, another Seleucid admiral, tried to map the seas around India — though he made the rather ambitious error of claiming that the Indian Ocean connected directly to the Caspian Sea.

Most of these accounts survive only in fragments, often quoted or critiqued by later writers. One of them, Strabo, writing in the 1st century BCE, didn’t buy into all of it.

He was openly skeptical of Deimachus and Megasthenes, calling their work too full of fables — though he still went on to repeat most of what Megasthenes wrote, which is weird, but hey, whatever. A little inconsistent, but not that unusual for the time. He did, however, put more faith in Patrocles and Eratosthenes, who, in his view, dealt more with geography than mythology.

According to Strabo, not long after Augustus took control of Egypt, while Gallus was Prefect of Egypt (26–24 BC), up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to modern-day India:

"At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Ethiopia, and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise."

In a really interesting excerpt, Strabo paints a picture of Indian festivals that sounded like a mix of a royal parade and a high-budget Bollywood film:

“Elephants adorned with gold and silver… gold vessels, drinking-cups, garments interwoven with gold… tame lions, buffaloes, and birds with variegated plumage.”

He was either impressed or just mad that his toga wasn’t embroidered with emeralds.

Jokes apart, by the end of the 2nd century BCE, direct contact had picked up.

Eudoxus of Cyzicus sailed to India, as did a mariner named Hippalus, who figured out the wind systems (monsoons) and helped open up sea trade between the Red Sea and the southern coast of India.

Bit by bit, the fog began to clear — and for the Greeks, India shifted from a place of myth to a place they could reach, describe, and attempt to understand.

Now we’ll take a detour to explore Arrian’s account of Ancient India. Why Arrian’s account, among so many others? There are a few good reasons for that — as you’ll see in a moment.

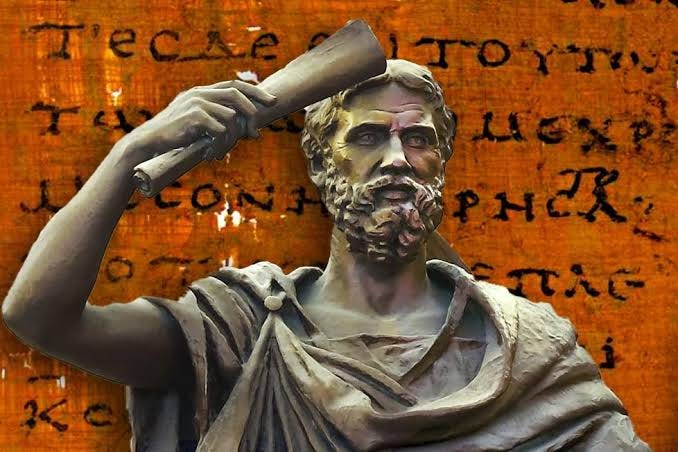

Arrian wasn’t your average Greek historian.

Born in the 2nd century CE, centuries after Alexander the Great had already marched across the known world, Arrian took it upon himself to write Indica, a kind of historical travelogue.

This travelogue was to be about India through the eyes of Alexander’s expedition.

Now, Arrian didn’t personally visit India. But he did something nearly as valuable — he compiled the observations of those who did, especially Nearchus, one of Alexander the Great’s admirals.

He also drew from earlier authors, including Eratosthenes and Megasthenes (whose own work, also called Indica, shaped Greek views of India for generations).

Most of their original texts are lost to us, but Arrian, writing a few centuries later, stitches together their observations into a neat little package. And thus, through their eyes, and through Arrian’s words, we get one of the earliest detailed Greco-Roman accounts of India.

What’s interesting is how similar all of their accounts are. The differences are minor — some names, a few exotic animals dialed up for dramatic effect — but the overall picture of India stays remarkably consistent across the board. Which is exactly why we’re focusing on Arrian.

By summarising the others, he saves us the trouble of chasing down each account individually. He gives us the broad strokes: the geography, the customs, the political systems, and the oddities that left the Greeks both confused and fascinated.

Arrian’s Indica opens with geography. He marvels at the Indus and the Ganges, likening them to the Danube and the Nile.

Then come the older tales: of Heracles and Dionysus, who, according to Greek legend, had already conquered India long before Alexander. This introduction pretty much mirrors the one in Megasthenes’ Indika.

Arrian then goes on to describe Indian society: its castes, customs, and hunting methods.

He lists animals and oddities, then shifts into a detailed retelling of Nearchus’ naval journey from India to Babylon — complete with strange tribes, sea battles, and long stretches of coastline.

Occasionally, he pauses to describe the people they encountered, like the fish-eating Ichthyophagi.

And finally, he ends with Nearchus reuniting with Alexander and being honored for surviving the journey.

Now, not everything in the Indica is spot-on. Some things are accurate, some are exaggerated & a few are just… strange.

But it offers us a useful look at how the Greeks & Romans thought about India. It’s as much a mirror of their imagination as it is a record of Indian reality.

Take Arrian’s very first impression about how Indians looked. He makes a pointed distinction between North & South Indians:

"The southern Indians resemble the Ethiopians a good deal, and, are black of countenance, and their hair black also, only they are not as snub-nosed or so woolly-haired as the Ethiopians; but the northern Indians are most like the Egyptian in appearance."

That mix of observation and stereotyping tells us less about Indians and more about the reference points the Greeks were working with.

For the Greeks, Ethiopians and Egyptians were the outer markers of the known world. India sat just beyond, so it was compared to what they already knew.

"The Indians in shape are thin and tall and much lighter in movement than the rest of mankind."

This is a passing comment about the physicality of Indians, but it tells us something too. The Greeks saw Indians as different, but not necessarily inferior — just distinct, & sometimes admirable.

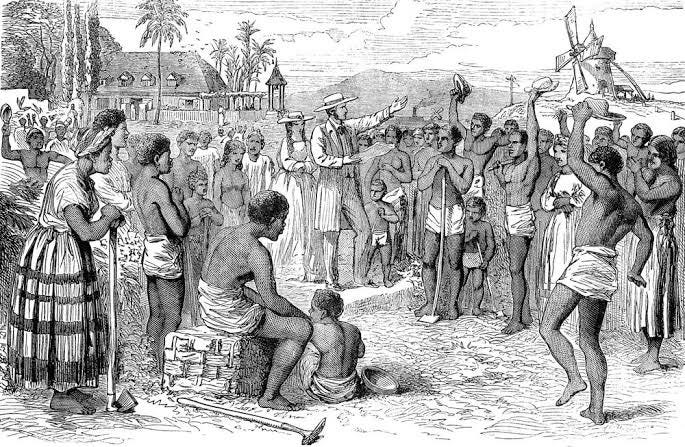

He then makes a claim about slavery in ancient Indian society that in today’s world, would raise a LOT of eyebrows.

"This also is remarkable in India, that all Indians are free, and no Indian at all is a slave. In this the Indians agree with the Lacedaemonians. Yet the Lacedaemonians have helots for slaves, who perform the duties of slaves; but the Indians have no slaves at all, much less is any Indian a slave."

Arrian claims that India had no slavery whatsoever — a point that’s also echoed by the likes of Megasthenes, Strabo, Eratosthenes, and others we’ve already met. What’s striking is how genuinely stunned Arrian seems by this.

He even compares Indians to the Spartans, who supposedly didn’t do slavery either — except they, um, did. They had helots, who were basically slaves with a slightly more poetic job description.

To someone coming from a world where slavery was baked into everyday life, the idea of a society functioning without it was both baffling and oddly admirable.

Arrian uses it to paint Indian society as unusually moral, even ideal. That theme of moral superiority pops up again & again in his writings.

It’s a flattering picture that reveals more about Greek perceptions than Indian policy. Take this quote for instance:

"No Indian ever went outside his own country on a warlike expedition, so righteous were they."

The idea that an entire civilisation could be powerful, advanced, and yet not expansionist was, to them, remarkable. (He wasn’t exactly right, of course, but hey, in Arrian’s defence, he’s clear that he prefers vibes over facts).

Other parts of Indica hint at Indian values. For example, let’s take funerals.

"Indians do not put up memorials to the dead; but they regard their virtues as sufficient memorials for the departed, and the songs which they sing at their funerals."

The Greeks built statues and tombs to honour their ancestors. Meanwhile, Indians, Arrian writes, honoured the dead through song and virtue (which kinda slaps, ngl).

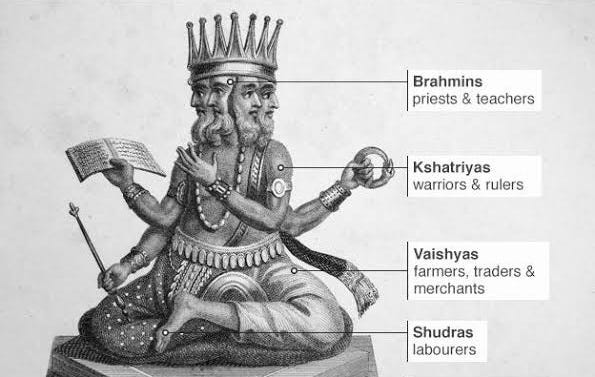

And of course, caste gets a mention.

"The Indians generally are divided into seven castes, the wise men, farmers, herdsmen, artisans and shopkeepers, soldiers, overlookers, and government officials including army and navy officers."

The number is a little more than the usual four we hear about, which leads to a lot of interesting implications.

Either way, it shows that even 2,000 years ago, outsiders were trying to make sense of India’s social jigsaw puzzle.

So what do we make of Indica? Not a guidebook to ancient India, certainly.

But it is a guide to how India was seen by the Greeks and Romans — how it puzzled them, impressed them, and challenged their assumptions.

That alone makes it worth reading. So go read it. Or don’t. Read something else. Scroll endlessly and rot your brain, maybe. But seriously, go pick up a book and read.

Great article. Whenever I read Greek philosophical literature it seems to me very speculative and cloudy. But, Indian metaphysics and philosophy have such an illuminating characteristic and unmatched breadth and depth. And there is a lot of potential for reconstructing Greco-Roman paganism and philosophy based off the long-preserved Vedic tradition.